Historically, you would have gotten good returns by simply holding a target percentage of your portfolio in stocks over many years, keeping the rest in 10-year bonds, and rebalancing periodically if the percentages drifted from your target. However, you would have suffered many drawdowns, sometimes extreme, lasting months or years. A week ago, I gave some examples as part of a series that started with my June 3 post for current U.S. markets, What Now: Sell, Rebalance, or Rotate?

This week's posts will introduce rotation as an an altenative to rebalancing. Today's examples are for U.S. stock and bond markets dating back to 1919. Four investment strategies are applied to this 100-year period:

This week's posts will introduce rotation as an an altenative to rebalancing. Today's examples are for U.S. stock and bond markets dating back to 1919. Four investment strategies are applied to this 100-year period:

- 100% in the S&P 500, with dividends reinvested.

- 100% in 10-year Treasury bonds with interest reinvested.

- 60% in the S&P 500 and 40% in 10-year Treasuries. At the end of each month, either reinvest the income in its source or, if the percentage in stocks has drifted to 55% or 65%, then rebalance stocks and bonds to their respective targets.

- Either 100% in the S&P 500 or 100% in 10-year Treasuries, according to their recent performance, checked at the end of each month.

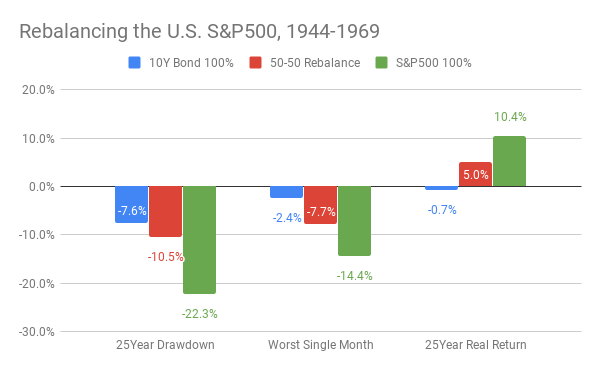

Comparing the strategies over the 100-year period from April 1919 to March 2019, 60-40 rebalancing and 100-or-0 rotation were virtually identical in one key way: over the long term, their equity exposures were virtually the same, 60.9% for rebalancing and 60.6% for rotation. In both cases, the portfolio tended to drift more toward stocks than toward bonds. For rebalancing, the long-term exposure to stocks was therefore slightly above the target of 60%. For rotation, the similar outcome over the full 100 years is an interesting coincidence. However, over shorter 25-year intervals, the stock-exposure of 100-or-0 rotation was variable.

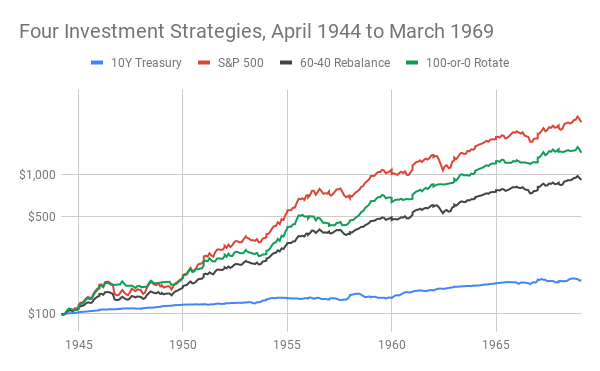

Between 1944 and 1969 (depicted above), 100-or-0 rotation was 69% in stocks, on average. That happened because during these years, stocks strongly outperformed bonds. (See this earlier post for some possible reasons.) Then, continuously holding 100% in the S&P 500 would have been the best strategy; rotation often avoided bonds and thus out-performed rebalancing; and Treasuries were exceptionally weak, actually falling behind the inflation rate.

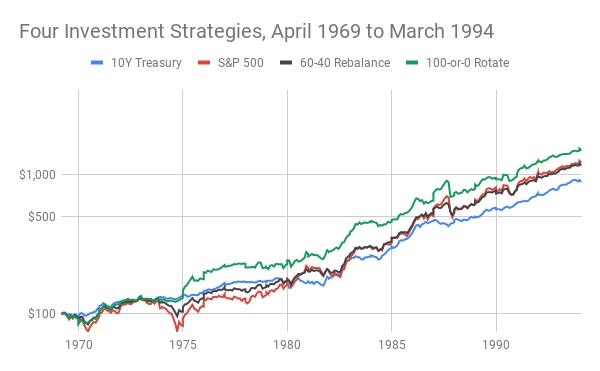

The next 25 years told a different story, as illustrated below. A sharp recession in the mid-1970's, followed by high inflation and high interest rates, then by prolonged rate cuts, combined overall to make the total return of bonds competitive with stock-returns. The strategy of 100-or-0 rotation responded in kind, allocating even-handedly, with an average stock-exposure of 53%. For the full 25 years, rotation beat all the other strategies, not by putting all its eggs in one basket, or by juggling two baskets at all times, but by opting periodically for the basket that better suited the changing financial environment.

The next 25 years told a different story, as illustrated below. A sharp recession in the mid-1970's, followed by high inflation and high interest rates, then by prolonged rate cuts, combined overall to make the total return of bonds competitive with stock-returns. The strategy of 100-or-0 rotation responded in kind, allocating even-handedly, with an average stock-exposure of 53%. For the full 25 years, rotation beat all the other strategies, not by putting all its eggs in one basket, or by juggling two baskets at all times, but by opting periodically for the basket that better suited the changing financial environment.

The four 25-year periods since 1919 exhibited a variety of environments, including the two described above; the bull market of the 1920's and Great Depression of the 1930's; and the dot-com bubble, Great Recession, and recent bull market of the 21st century. Across it all, if given 25 years, a strategy of 100-or-0 Rotation ...

In forthcoming posts, I'll continue this introduction to rotation as an investment strategy, examining questions like these:

- Beat 60-40 Rebalancing, every time

- Beat 100% invested in the S&P 500, three of four times

- Beat 100% placed in 10-year Treasuries, every time

- Beat inflation handily, for every 25-year period

In forthcoming posts, I'll continue this introduction to rotation as an investment strategy, examining questions like these:

- Using both raw returns and risk-adjusted metrics, how did rotation fare across 25-year periods and across countries?

- What about drawdowns, as in "flash-crashes" and major recessions? Did rotation handle them better than rebalancing?

- Is 100-or-0 the best way to do rotation, at all times and for all investors? Or would less drastic exchanges be better, depending on circumstances?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed