Accurately measuring whether stocks are over- or under-valued is hard enough. Yet even if that problem were solved, others would remain. An indicator that predicts a big change in stock prices over the near term is likely to have a wild margin of error. Longer term, the error-rate may decline, leading to a safer, more confident prediction, but the price-change will also fade to a smaller size. Is there any way to have it all: calculate a credible benefit, capture it safely, and bank it soon?

A Good Estimate

Earlier posts on this topic proposed how best to measure whether stocks are over- or under-valued. To recap, three ideas are key.

- According to solid academic studies, Shiller's ten-year CAPE is a good starting point. Andrew Ang's Asset Management (chapter 8, section 5.2 ) explains CAPE's uniquely reliable, if somewhat modest, power as a predictor

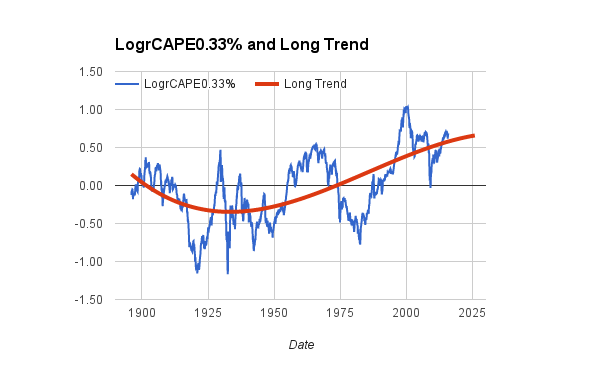

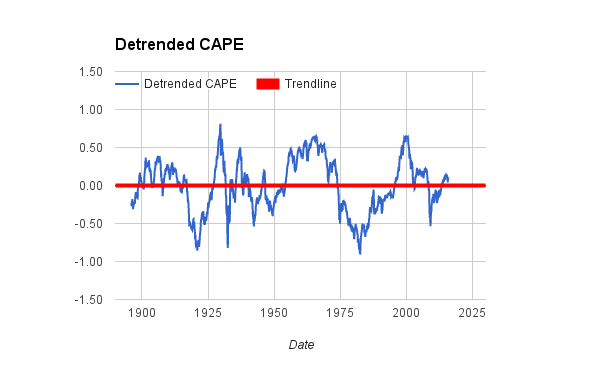

- The standard measurement of CAPE can be improved by computing it over a longer period than ten years with a method that gradually reduces the weight of older data, and by applying logarithms to ensure that high and low readings are judged evenly.

- Some credence should be given to the possibility that CAPE has its own long-term trend. Predictions can be improve by filtering out this trend, at least partially.

A Safe Benefit

As of early 2016, the corrected CAPE is rather high, approximately +0.4. A corrected CAPE this much above a neutral value of zero implies over-valued stocks, hence a risk that future returns from stocks will be less than normal. Given this reading, how much weakness in stock prices might one expect? Is a swift decline likely, or an extended period of lackluster gains, or what? The answer, it turns out, depends on whether the goal is to predict changes for next year, the next decade, or even farther into the future.

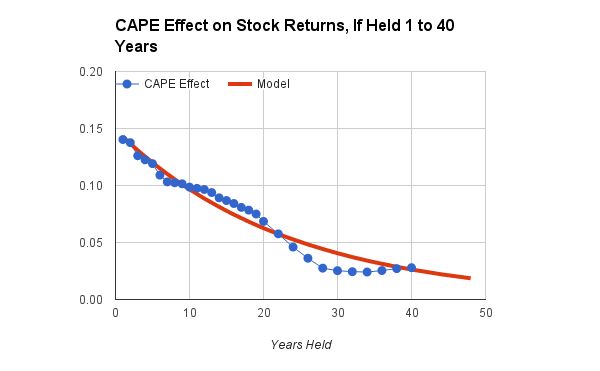

In the chart above, the CAPE Effect is a multiplier that tells how much to adjust the future returns of U.S. stocks, given a value of the corrected CAPE. The blue dots are actual data points from a comprehensive study covering the period from 1896 through 2015. The red line is a statistically fitted model used in our calculators.*

Given corrected CAPE's early 2016 value of +0.4, a one-year forecast is an effect of roughly 0.4 * 0.14 = 0.056 on a log scale. The spreadsheet function EXP(0.056) converts back to a percentage, 5.8%, which is the predicted reduction in real (inflation-adjusted) stock-returns over the next year, because of the current over-valuation. For the 1896-2015 period of the study, compound real returns were about 6.6% per year, so the year-ahead prediction is a return of 6.6% - 5.8%, or a meager 0.8% better than inflation, including reinvested dividends. With economists currently predicting an inflation rate of about 2%, the nominal return would be 2.8%. That's less than the historical return of ten-year Treasury bonds.

If U.S. stocks were held longer, for the next 20 years, the chart predicts the effect would still be negative but less drastic, roughly half as large. The compound, inflation-adjusted return would be reduced about 2.6%. Instead of enjoying average real returns of 6.6% annually for two decades, one's portfolio of U.S. stocks would grow 6.5% - 2.6% = 4.0% per year, above inflation. That's not shabby. It's better than bonds, but below average for the long-term performance of stocks.

What the chart says, in short, is that buying stocks today is like paying a premium price for a house when real-estate is hot. Even after holding the investment for many years, one's annualized profits may be tepid.

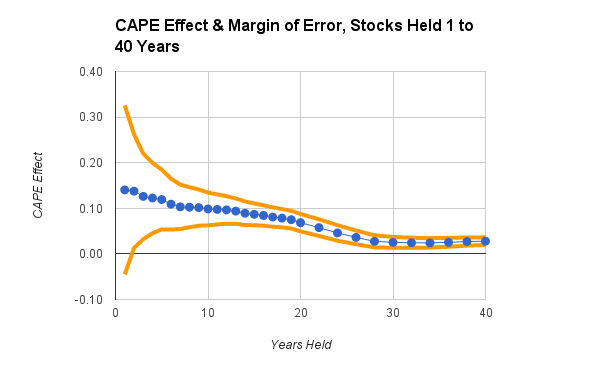

There's a problem, however, in making decisions like these. The next chart shows why. It presents the same data points (the blue dots), bracketed by their margins of error.** Statistically, most of the historical data falls between the upper and lower margins of error (the orange lines). A big gap between the lines implies great uncertainty; a narrow gap means the prediction is more trustworthy.

Given corrected CAPE's early 2016 value of +0.4, a one-year forecast is an effect of roughly 0.4 * 0.14 = 0.056 on a log scale. The spreadsheet function EXP(0.056) converts back to a percentage, 5.8%, which is the predicted reduction in real (inflation-adjusted) stock-returns over the next year, because of the current over-valuation. For the 1896-2015 period of the study, compound real returns were about 6.6% per year, so the year-ahead prediction is a return of 6.6% - 5.8%, or a meager 0.8% better than inflation, including reinvested dividends. With economists currently predicting an inflation rate of about 2%, the nominal return would be 2.8%. That's less than the historical return of ten-year Treasury bonds.

If U.S. stocks were held longer, for the next 20 years, the chart predicts the effect would still be negative but less drastic, roughly half as large. The compound, inflation-adjusted return would be reduced about 2.6%. Instead of enjoying average real returns of 6.6% annually for two decades, one's portfolio of U.S. stocks would grow 6.5% - 2.6% = 4.0% per year, above inflation. That's not shabby. It's better than bonds, but below average for the long-term performance of stocks.

What the chart says, in short, is that buying stocks today is like paying a premium price for a house when real-estate is hot. Even after holding the investment for many years, one's annualized profits may be tepid.

There's a problem, however, in making decisions like these. The next chart shows why. It presents the same data points (the blue dots), bracketed by their margins of error.** Statistically, most of the historical data falls between the upper and lower margins of error (the orange lines). A big gap between the lines implies great uncertainty; a narrow gap means the prediction is more trustworthy.

For stock investments held one year, the margin of error is extreme. While the average one-year effect might be alluring, actual one-year results have often been very different, in both directions. Evidently, a short-term forecast is both big and wild. It's like predicting tomorrow's weather to be a 90% chance of rain, maybe a steady downpour, maybe a brief drizzle.

At the other extreme, for a holding period of 30 to 40 years, the prediction is much more precise, thanks to a tiny margin of error. It's a safe forecast, but the effect has become small. Now the weather forecast is for a certainty of rain this season, totaling 5 to 6 inches, but there's no telling which days will be wet.

The ideal case would be to find the points on the chart where the range of uncertainty excludes a zero effect, which appears to happen after about three or four years, yet the effect-size remains large enough to matter, which seems possible up to the mid-twenties.

At the other extreme, for a holding period of 30 to 40 years, the prediction is much more precise, thanks to a tiny margin of error. It's a safe forecast, but the effect has become small. Now the weather forecast is for a certainty of rain this season, totaling 5 to 6 inches, but there's no telling which days will be wet.

The ideal case would be to find the points on the chart where the range of uncertainty excludes a zero effect, which appears to happen after about three or four years, yet the effect-size remains large enough to matter, which seems possible up to the mid-twenties.

A Reasonable Time

Our calculators quantify these ideas by giving a weight to the corrected CAPE.*** As the margin of error decreases, the weight goes up. At the same time, as the effect-size declines, the weight goes down. The statistical model finds an optimal way to calculate the weights, and, it so happens, the weight steadily increases from one to 24 years, then very gradually declines.

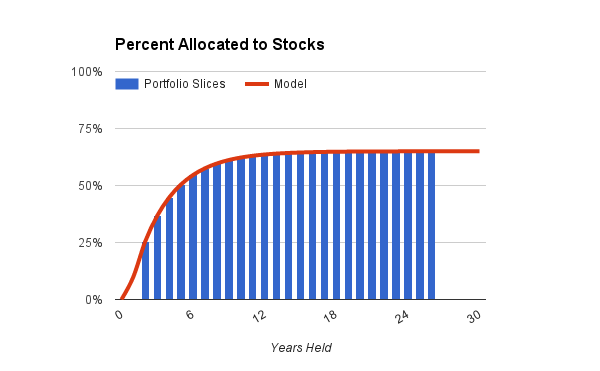

For a concrete example, start with the chart below. It shows how our calculators simulate the portfolio of a hypothetical investor who matches this description:

For a concrete example, start with the chart below. It shows how our calculators simulate the portfolio of a hypothetical investor who matches this description:

- She has moderate preferences. Her goal is a compromise between maximizing gains and minimizing losses, and she is somewhat able to tolerate ups and downs in her investments.

- She plans to start spending her savings in two years, when she will retire. Given her health status and current age, she expects to continue spending for a total of 25 years.

- If she had children, she might add another five or ten years of spending, to allow her heirs to spend-down any residual savings after she dies. But she has no children and prefers to maximize her retirement budget by spending all her investments. Her home equity provides a safety net.

The calculator's statistical model, shown by the red line, sets the investor's exposure to stocks, given her preferences and the time remaining until invested funds will be spent.^ The blue bars are slices or portions of her portfolio, one for each year of anticipated spending.

Because this particular investor's preferences are moderate, the calculator assigns 65% as her maximum exposure to stocks, for investments held 20 years or longer. Anything not invested in stocks goes to bonds, at durations that depend on how soon the funds will be spent.

More than half the portfolio will be held 12 years or longer, and is therefor invested near the maximum level of 65% stocks and 35% bonds. The other half is invested with increasing caution, depending on proximity to the retirement date. As the investor ages and begins to spend her savings, the blue bars will, in effect, march to the left in the chart while staying under the model's red line, thus causing her portfolio to become more conservative over time. Right now, with retirement still two years away and many years of longevity on the horizon, her investments are, overall, about 60% in stocks.

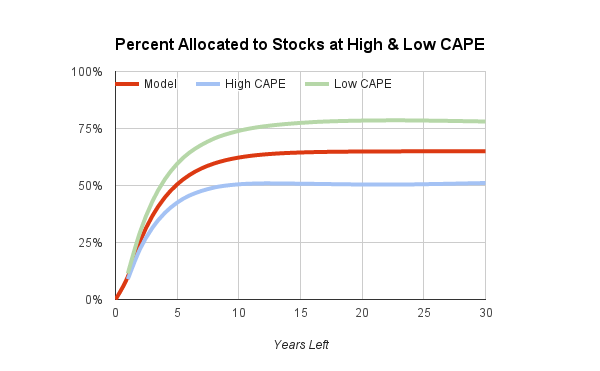

That's without any adjustment for stocks being over- or under-valued. The next chart shows how much this investor's profile would have changed, when adjusted by the corrected CAPE, had the current date been any year between 1920 and 2015. Over those 96 years, 80% of the data fell between the lines shown as High CAPE and Low CAPE (10% were even higher, 10% even lower).

Because this particular investor's preferences are moderate, the calculator assigns 65% as her maximum exposure to stocks, for investments held 20 years or longer. Anything not invested in stocks goes to bonds, at durations that depend on how soon the funds will be spent.

More than half the portfolio will be held 12 years or longer, and is therefor invested near the maximum level of 65% stocks and 35% bonds. The other half is invested with increasing caution, depending on proximity to the retirement date. As the investor ages and begins to spend her savings, the blue bars will, in effect, march to the left in the chart while staying under the model's red line, thus causing her portfolio to become more conservative over time. Right now, with retirement still two years away and many years of longevity on the horizon, her investments are, overall, about 60% in stocks.

That's without any adjustment for stocks being over- or under-valued. The next chart shows how much this investor's profile would have changed, when adjusted by the corrected CAPE, had the current date been any year between 1920 and 2015. Over those 96 years, 80% of the data fell between the lines shown as High CAPE and Low CAPE (10% were even higher, 10% even lower).

As it happens, the corrected CAPE in early 2016 is approaching the value marked by the blue line, where High CAPE means that stocks are over-valued. In times like these, the hypothetical investor's profile gets shifted to the blue line, where the maximum invested in stocks is adjusted down to about 50%. On the other hand, if today's corrected CAPE were like the green line in the chart, with stocks a real bargain (Low CAPE), then more than 75% would be invested in stocks to be held for a decade or more. Notice, however, what happens for near-term holdings that will be spent in two or three years. Here, the calculator makes hardly any adjustment for CAPE.

If the holding period were extended well beyond 30 years, the adjustment would diminish somewhat because the effect of CAPE would very gradually fade. But it would not vanish completely in any normal lifetime. To give a specific example, if you had bought stocks near the top of the dot-com bubble in late 1999, when over-valuation of stocks peaked, your returns, even if you held the stocks for many decades, would likely be poorer than if you had purchased at a more normal price.

One final note is important. Some time in the next decade or two, stocks could take a tumble. If they do, the corrected CAPE may fall to a level that recommends a higher-than-normal exposure to stocks. If you adjust your stock allocation periodically, perhaps every quarter or year, according to the calculator's then-current recommendations, the result will be to move some of your holdings in and out of stocks as they become cheap or expensive, taking into account your evolving plans to spend your savings. In that sense, today's relatively expensive stocks are not a permanent penalty for your portfolio. They are a reason for caution that will last only until more optimism is warranted.

If the holding period were extended well beyond 30 years, the adjustment would diminish somewhat because the effect of CAPE would very gradually fade. But it would not vanish completely in any normal lifetime. To give a specific example, if you had bought stocks near the top of the dot-com bubble in late 1999, when over-valuation of stocks peaked, your returns, even if you held the stocks for many decades, would likely be poorer than if you had purchased at a more normal price.

One final note is important. Some time in the next decade or two, stocks could take a tumble. If they do, the corrected CAPE may fall to a level that recommends a higher-than-normal exposure to stocks. If you adjust your stock allocation periodically, perhaps every quarter or year, according to the calculator's then-current recommendations, the result will be to move some of your holdings in and out of stocks as they become cheap or expensive, taking into account your evolving plans to spend your savings. In that sense, today's relatively expensive stocks are not a permanent penalty for your portfolio. They are a reason for caution that will last only until more optimism is warranted.

* The data for the study were monthly prices of the S&P 500, or a reasonable surrogate, and corresponding estimates of consumer inflation, from 1871 to 2015, as compiled by Robert Shiller. The period from 1871 to 1895 was used to initialize the values of the corrected CAPE. The plotted points in the chart are slopes from regressing LN(r) on LN(c), where r is the annualized real return on stocks, with dividends reinvested, and LN(c) is the corrected CAPE as described in an earlier post. The fitted line is a power function of the form s = -b * POWER( m, y ) where s is the slope; b and m are fitted constants; and y is the holding period in years.

** Statistically, the margin of error is the standard error of the least-squares estimated slope, on a natural-log scale.

*** The weight is k * s / e, where s is the slope; e, the standard error of the slope; and k, a fitted constant. All are on a natural-log scale. The weight is fitted to optimize the natural-log of the annualized real return.

^ The calculator's model for stock-allocations is an exponential function of the form:

p = q + u * ( 1 - EXP( - (y-1)/v) ),

where p is the portion allocated to stocks; q is a minimum allocation when there is one year left before spending starts; q + u is the upper limit or asymptote of the stock allocation; y is the holding period or "slice"; and v is a factor that controls the rate of rising from the minimum to the asymptote. As described here, this model worked better than other growth functions as a method of optimizing returns.

** Statistically, the margin of error is the standard error of the least-squares estimated slope, on a natural-log scale.

*** The weight is k * s / e, where s is the slope; e, the standard error of the slope; and k, a fitted constant. All are on a natural-log scale. The weight is fitted to optimize the natural-log of the annualized real return.

^ The calculator's model for stock-allocations is an exponential function of the form:

p = q + u * ( 1 - EXP( - (y-1)/v) ),

where p is the portion allocated to stocks; q is a minimum allocation when there is one year left before spending starts; q + u is the upper limit or asymptote of the stock allocation; y is the holding period or "slice"; and v is a factor that controls the rate of rising from the minimum to the asymptote. As described here, this model worked better than other growth functions as a method of optimizing returns.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed